The following was transcribed from this YouTube video: We need to 'gravitise' quantum mechanics, not quantise gravity | Roger Penrose | Full Interview

Penrose is 93 and in an amiable mood in this interview, so he goes into minor non-mathematical tangents from time to time. I've edited the following for clarity so that just the mathematical structure comes through:

Engelbert explained two things to me which were extremely important to me. One was that Maxwell's equations, the equations of electricity, magnetism and light, are conformally invariant, which means you don't need to scale -- size doesn't come into it. On the big scale and the small scale they're exactly the same. They're insensitive to change of scale. So I find that very beautiful. The other thing he told me was that in quantum field theory, the most important thing is the splitting of field amplitudes into positive and negative frequencies. I can't really go about being a little more technical what that means, but what it usually means to people is you take what's called the Fourier decomposition and then you take the positive part each time. So you've got different frequencies involved and you take each frequency and you split it into the positive/negative frequencies. And you do that all the way along. I didn't like that much because that splitting is not conformally invariant. And if you want to do it for Maxwell's theory, it would be much nicer to have a way of saying it which didn't involve all this Fourier decomposition.

So I thought, well, there is a way of doing that. You just think -- I should explain this all involves complex numbers -- quantum mechanics is absolutely bound up with complex numbers, which I may say is one of the things which attracted me to the subject. It's an extremely beautiful theory in mathematics. There are various things which -- to understand them properly -- you think of them in this complex number context. There are certain things which work so much better when you do that. And this is one example.

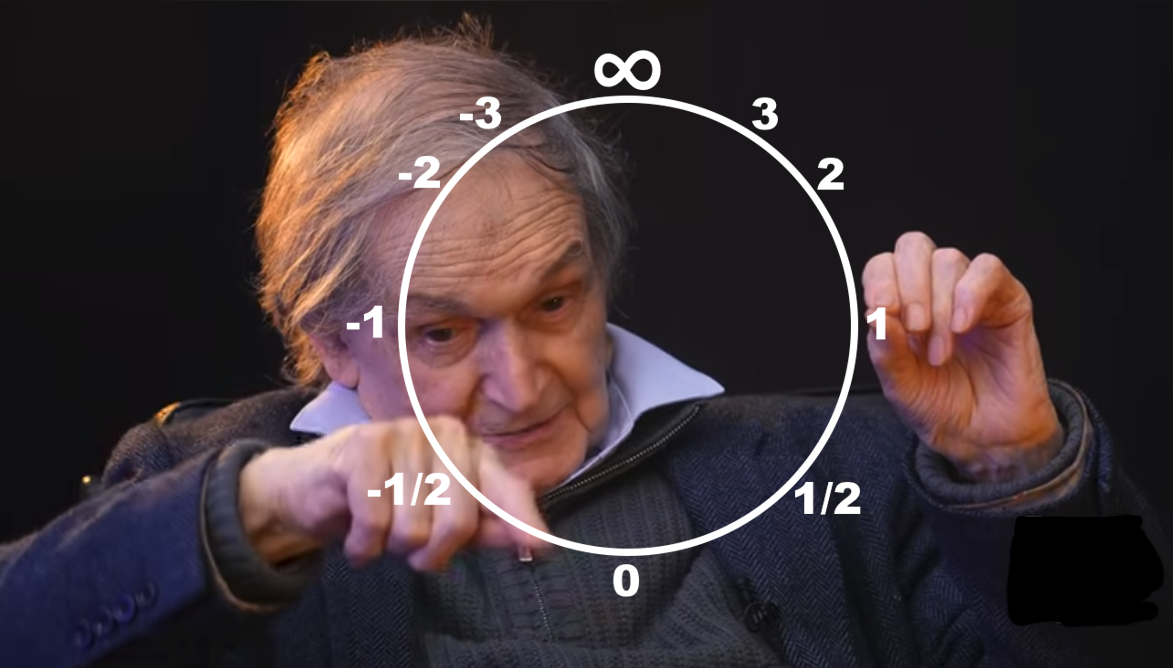

You think of the real numbers, together with infinity. So I'm conformally -- infinity is -- just like another number connects the positive ones and the negatives like a circle.

[He begins drawing a circle in the air with his hands; see image to the right]

You see: zero, one, two, three, four, when it gets closer and closer, a little more... infinity! And then minus infinity is the same point... minus two, minus one, zero. Beautiful circle, you see.

Think of that as the equator of a sphere. You have a function on that equator -- that's the real numbers -- and you look at the parts of that function which extends into the positive hemisphere and the part which extends into the negative hemisphere. One is the positive frequency and the other is a negative frequency.

I thought: "That's much more beautiful," the idea that you could talk about this fundamental feature of quantum theory in terms of this geometry of the sphere. The real numbers -- together with infinity -- cut it in half[1].

So what I was thinking: "I really don't want to do this for one dimensional time or something like that. I want to do it globally for the whole of space time."

What a silly idea, but that's what I thought. There must be a way of doing it for the whole of space time. There was a thing that I knew about called the forward tube, which is what happens in a complexified space time, but then you get eight dimensions and... nothing divides anything in half. It doesn't work at all. So I knew about it, but there was no help.

But you see, I knew of what Ivor had told me, and he described to me this class of solutions of Maxwell's equations that were based on these classes of light rays. When I say light ray, I'm thinking of the trajectory of a photon, if you like. So it moves along, but in the history of the space time, it's a line. So it's a space time line. So when I say light ray, that's what I mean. I call it Robinson congruence.

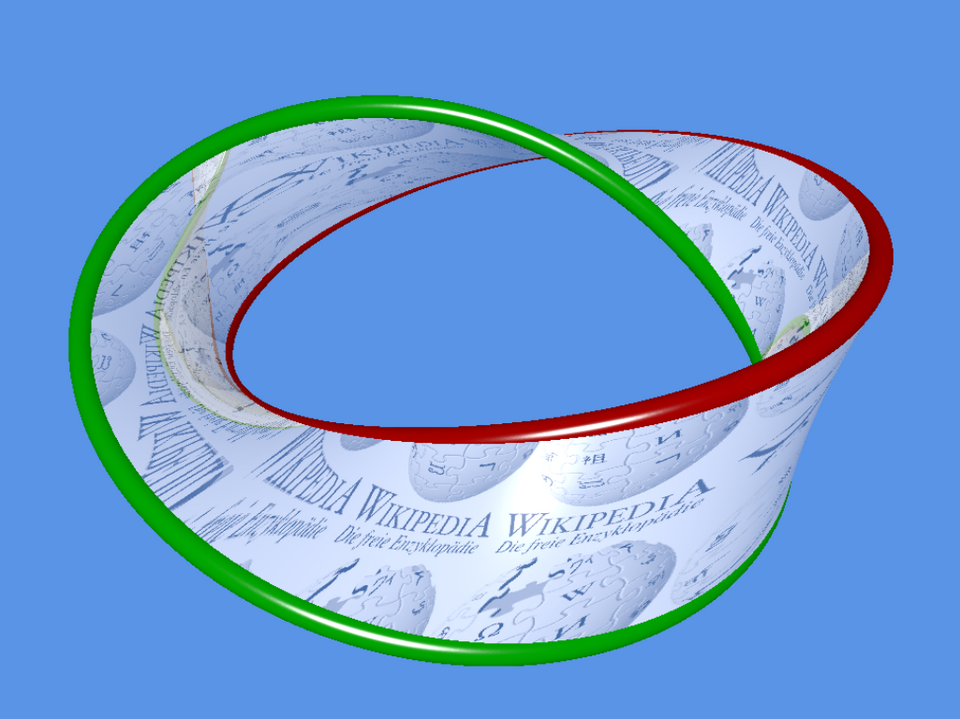

You take the light ray that all the other light rays meet. See, there all the other ones meet it and you construct your solution of Maxwell's equation on the basis of those lines. This is a very beautiful solution. But what you can also do is displace this light ray into the complex and the other ones are still there. They're still the ones that meet it. They sort of meet it -- in an imaginary way -- but they do still. And you get the same -- congruence as it's called -- but it twists around and it doesn't have any singularities. It doesn't meet the line. You see, where all the lines meet, it's a sort of singular place. But if you displace the line into the complex, they don't. They twist around in this amazing way. And I had sort of understood that configuration already.

It's as if from a three-dimensional terms, you can think of it in terms of what are called Clifford parallels. There's a certain construction done by this British mathematician... he discovered this amazing construction which is... you have to think of a sphere in four dimensions, so it's a three-dimensional surface in four dimensions. And in that surface, you have this family of circles, all of them which link each other in this amazing twisty way. And I sort of knew that I was describing that -- that the way they twist is the Clifford parallels.

It's as if from a three-dimensional terms, you can think of it in terms of what are called Clifford parallels. There's a certain construction done by this British mathematician... he discovered this amazing construction which is... you have to think of a sphere in four dimensions, so it's a three-dimensional surface in four dimensions. And in that surface, you have this family of circles, all of them which link each other in this amazing twisty way. And I sort of knew that I was describing that -- that the way they twist is the Clifford parallels.

And so I thought to myself, how many dimensions did that space have? How many of these twisting families are there compared with the number of light rays are there? And I thought, gosh, it's just six. Whereas the number of light rays, how many dimensions is the space of light rays, how many parameters do you need to describe the light rays? It's five. How do you ascribe the Robinson congruence? Six. One more. Why is that exciting to me? Because I'm looking for a space where the real things that you talk about -- that's the light rays -- I should be thinking not points but light rays. That was the key. Think of light rays. Don't think of points.

The points of space time are four dimensional, and if you complexify, it's eight dimensional. It's no use to me. But I think of the light rays and then I see them in the subtle Robinson way, then I only get six dimensions. So my space is split into two halves, the ones which twist right handed, the ones which twist left handed, and the ones which don't twist, which are the light rays. And that was my key thought.

Note(s)

- ^ I sat up bolt upright when I heard him say these words: "...geometry of the sphere. The real numbers -- together with infinity -- cut it in half" as I immediately thought of the Riemann zeta function, which uses an infinite series operating on a pattern of real halves combined with imaginary numbers. But alas, that manifests as a spiral, not a sphere. Still intriguing, maybe there's a link in there...